Introduction to Lattices and Learning With Errors

Imagine waking up one day to find that all your online passwords, secure connections, and encrypted data are suddenly vulnerable. This isn’t the plot of a sci-fi movie – it’s a real concern in the world of cybersecurity. In the world of cryptography, a seismic shift is underway. The looming advent of quantum computers threatens to break many of our current encryption methods, pushing researchers to develop new, quantum-resistant cryptographic systems. At the forefront of this effort are lattice-based cryptographic schemes, with the Learning With Errors (LWE) problem as a cornerstone.

In this series of occasional, brief posts, I will be sharing my notes on the topic. Here are some of the topics I plan to cover (hopefully someday!):

- Lattices and their properties

- Hard problems on lattices like SVP, CVP, BDD, GAP versions etc.

- Usage in cryptography

- SIS and LWE

- Worst case to average case reductions (at least classical one)

- Cryptosystems based on LWE

- NIST Candidates

- CRYSTALS suite (at least brief mention of their working)

From here, two paths emerge: Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE), the holy grail of cryptography; or Complexity Theory, exploring why these problems are considered “hard”. Currently, my focus is on FHE.

Point to Note: I have been studying lattices since February last year. These blogs are my personal notes and reflections on my understanding so far. Mistakes are inevitable, as learning is a continuous journey. If you spot any inaccuracies or have suggestions, please feel free to educate me. We are all students of this vast and intricate matrix.

Traditional Cryptography: RSA and Diffie-Hellman

Currently, most of the cryptography used in our daily lives relies on protocols like RSA and Diffie-Hellman.

RSA

RSA is based on the mathematical assumption that factoring a very large number into its prime factors is computationally difficult. This hardness is what secures RSA encryption, making it feasible to encrypt data with a public key while only the corresponding private key, which is derived from these prime factors, can decrypt it.

Diffie-Hellman

Diffie-Hellman is based on the discrete logarithm problem. This problem assumes that given a number $y$, which is calculated as:

\[y = g^x \mod p\]where \(g\) is a generator, \(x\) is an exponent, and \(p\) is the modulus is a prime number, it is computationally hard to determine the value of \(x\).

In simpler terms, while it is easy to compute \(y\) from \(g\), \(x\), and \(p\), it is very difficult to reverse this process and find \(x\) given only \(g\), \(y\), and \(p\). This discrete logarithm problem underlies the security of the Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol, which allows two parties to securely share a common secret over an insecure channel without having prior knowledge of each other’s private keys.

Both RSA and Diffie-Hellman are fundamental to many encryption systems used in securing internet communications, digital signatures, and more.

The Quantum Threat: Shor’s Algorithm

In 1994, Peter Shor developed a quantum algorithm that efficiently solves integer factorization and discrete logarithm problems in polynomial time. This breakthrough poses a significant threat to widely used cryptographic protocols:

- RSA: Based on the difficulty of factoring large numbers.

- Diffie-Hellman key exchange: Relies on the discrete logarithm problem.

- Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC): The elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem can be solved efficiently.

Once large-scale quantum computers become a reality, these protocols will be effectively broken, compromising much of our current digital security infrastructure.

Enter Lattices: A Quantum-Resistant Foundation

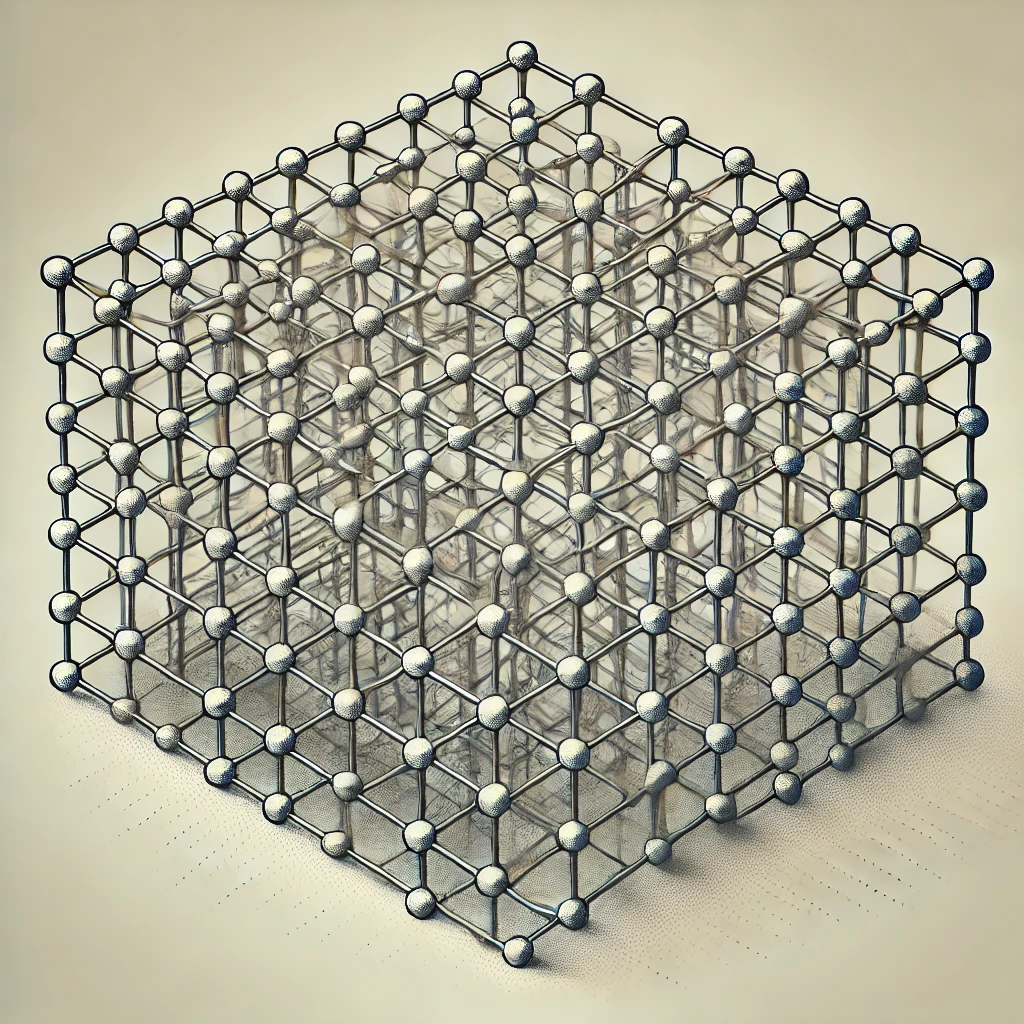

This is where lattices come into play. In mathematics, a lattice is a regularly spaced grid of points stretching out to infinity. Imagine a vast checkerboard extending in all directions. These structures turn out to have some fascinating properties that make them excellent building blocks for post-quantum cryptography.

To understand lattices mathematically, think of a pattern of points in space that repeats infinitely. Imagine a grid where every point is equally spaced from its neighbors, extending in all directions forever. To describe this mathematically, we need:

- A starting point (usually the origin, or (0,0,0) in 3D space)

- A set of directions that tell us how to move from one point to another

These directions are called “basis vectors”. They’re like the fundamental building blocks of our lattice. Every point in the lattice can be reached by following these directions in different combinations. Here’s a more formal definition:

A lattice is the set of all points that can be reached by:

a) Starting at the origin

b) Moving along the basis vectors

c) Using only whole number multiples of these vectors

A lattice in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) is formally defined as the set:

\(L(b_1, ..., b_n)\) = \(\left\{ \sum_{i=1}^n x_i b_i : x_i \in \mathbb{Z} \right\}\)

Where \((b_1, ..., b_n)\) are linearly independent vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^n\).

A set \(B\) = \((b_1, ..., b_n)\) is known as the basis of the matrix.

Ajtai’s Seminal Work: A Cryptographic Breakthrough

In 1996, Miklós Ajtai made a groundbreaking discovery that revolutionized the field of cryptography. He demonstrated a connection between the average-case complexity of certain lattice problems and their worst-case complexity.

This result was seminal for cryptography for several reasons:

- It provided a theoretical foundation for the security of lattice-based cryptosystems.

- It showed that solving random instances of certain lattice problems is as hard as solving the hardest instances of these problems.

- It opened the door for creating cryptographic schemes based on well-studied mathematical problems.

Ajtai’s work laid the groundwork for developing cryptographic systems that are believed to be secure even against quantum computers.

Key Concepts in Lattice-Based Cryptography

-

Dual Lattice: For every lattice (\Lambda), there’s a dual lattice (\Lambda^*) defined as:

[ \Lambda^* = \left{ y \in \mathbb{R}^n : \langle x, y \rangle \in \mathbb{Z} \text{ for all } x \in \Lambda \right} ]

-

Discrete Gaussian Distribution: This distribution, denoted (D_{\Lambda, t}), assigns probability mass proportional to (e^{-\pi |x/t|^2}) to each point (x \in \Lambda).

-

Fundamental Parallelepiped and Lattice Determinant: For a matrix (B), the fundamental parallelepiped (P(B)) is defined as:

[ P(B) = { Bx : x \in [0, 1)^n } ]

The determinant of a lattice (L(B)) is ( \det(L) = \det(B) ). -

Minkowski’s Theorems: These provide important bounds on lattice vectors and volumes.

-

Computational Problems:

- Shortest Vector Problem (SVP): Find the shortest non-zero vector in a lattice.

- Closest Vector Problem (CVP): Find the closest lattice vector to a given point.

These problems are believed to be hard for both classical and quantum computers, forming the basis for lattice-based cryptography. I will delve deeper into these in the next post.